*** ENGLISH VERSION BELOW ***

Madrid, sabato sera all'imbrunire, con le luci della città che si accendono come fiammelle. Dall'ingresso dello chapiteau del Circo de Los Horrores filtra una lieve luminescenza rossa, come se al di là il mondo avesse un'altra tinta, accesa e inquietante.

Dentro, un pianista elegantemente vestito in viola, suona con mani agili, mentre tutte le forme sono rosse di luce soffusa. Poi entrano in scena varie figure, che scendono tra il pubblico come apparizioni.

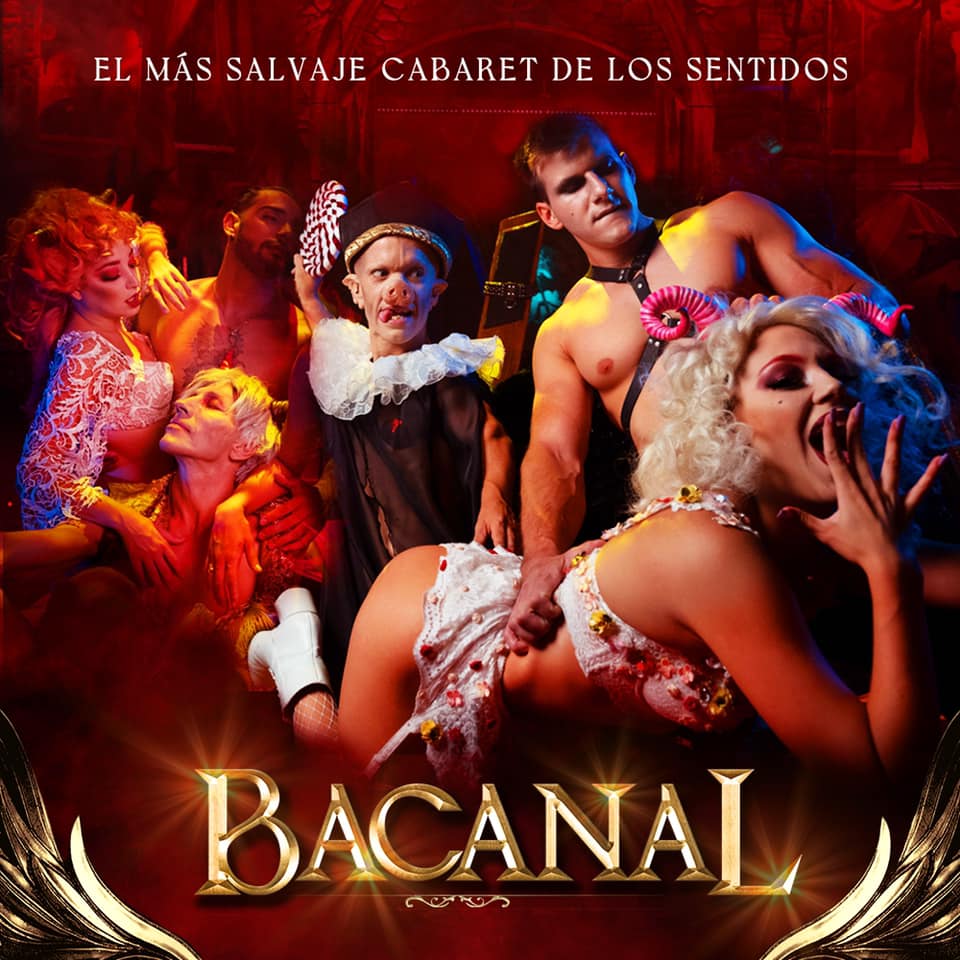

Mi si avvicina una sensuale cortigiana con le corna ritorte, il fare scherzoso, attraente e spaventosa; poco lontano un'altra dama prosperosa abbassa di colpo la guépière per mostrare compiaciuta i suoi tre seni; sullo sfondo, dentro la scena, uomini dai muscoli scolpiti e le ali nere, donne provocanti adagiate sui sofà, un nano che si agita e ride, mentre Nebula, figlia di Lucifero, porta uno schiavo seminudo al guinzaglio. Quando la musica sale entra in scena Lucifero dalle corna caprine, con il volto bianco, gli occhi inumani, la profonda voce roca, e lo spettacolo ha inizio.

Lucifero tira i fili del gioco, tiene il pubblico sospeso alla sua voce oltraggiosa, lo provoca, interroga, giocando abilmente come il gatto con il topo, fino a scatenare risa incontenibili, simile a un antico clown bianco autoritario e temibile.

Quando le risate si spengono, iniziano i giochi icariani, perché Bacanal è circo vero, e propone numeri tecnicamente difficili, altamente spettacolari, immersi in atmosfere erotiche e oscure.

Ci sono balletti osceni, ma dalle movenze sinuose ed eleganti, canzoni goliardiche come l'inno alla sitofilia (feticismo legato al cibo), ma anche un numero di palo cinese tecnicamente perfetto, che tuttavia ricorda una pole dance erotica; un'esibizione di coppia al trapezio singolo di grande effetto, dove lo spettatore non sa più dove guardare: sotto agli acrobati, su un enorme letto, vengono simulati amplessi, e ai lati della scena si svolgono giochi sadomaso.

Ci sono balletti osceni, ma dalle movenze sinuose ed eleganti, canzoni goliardiche come l'inno alla sitofilia (feticismo legato al cibo), ma anche un numero di palo cinese tecnicamente perfetto, che tuttavia ricorda una pole dance erotica; un'esibizione di coppia al trapezio singolo di grande effetto, dove lo spettatore non sa più dove guardare: sotto agli acrobati, su un enorme letto, vengono simulati amplessi, e ai lati della scena si svolgono giochi sadomaso.

Quando Lucifero dichiara l'intervallo, penso che già la prima parte, da sola, sia valsa la trasferta a Madrid.

Il secondo atto si apre con atmosfere più cupe e spaventose. Le streghe celebrano il sabba e invocano Bafometto, antica divinità pagana assimilata al diavolo, che appare con la cappa nera e le corna sul capo, per esibirsi in un impressionante numero di cinghie aeree, volteggiando fin sopra le teste del pubblico, mentre sotto le streghe ballano, mostrando i corpi nudi, appena velati, come sfocati dalle nebbie del tempo, quasi fossero visioni.

Segue un funereo numero di contorsionismo, che vede sullo sfondo le terribili maschere appuntite dei medici della peste. Le movenze estreme di un contorsionista, con la giusta ambientazione e musica, possono essere impressionanti: ho sentito nei momenti salienti qualcuno del pubblico urlare, come se vedesse ossa frantumate e articolazioni irrimediabilmente slogate.

Lucifero torna in scena per celebrare un matrimonio "del lato oscuro" e pesca una coppia di sposi nel pubblico; si tratta di una farsa dissacrante e divertente, dove il diavolo indaga gelosie, trascorsi, abitudini sessuali, affinità e divergenze, creando situazioni esilaranti. Non è affatto facile far ridere svelando gusti e abitudini sessuali, che nella nostra cultura sono privati, quasi segreti. Se ci si riesce, le risate che si creano hanno un timbro particolare: sono leggere e liberatorie, quasi sconfiggessero il pudore e un recondito senso del peccato.

Nella parte finale trova la sua perfetta collocazione anche un numero di filo molle che definirei spaventoso, visto che sul filo l'artista finisce per mettersi a testa in giù, in bilico su una scala.

L'ultima esibizione è un mano a mano in cui uno dei due artisti, bravissimo, è disabile ed entra in scena su sedia a rotelle. Lucifero coglie l'occasione per impartire al pubblico un grande insegnamento. Spiega come si possa reagire alle crudeltà del destino, vincendo ogni difficoltà; invita a godersi l'oggi, a non angosciarsi per il domani, e svela la natura di Bacanal: una grande celebrazione della vita, in tutti i suoi aspetti, con le sue vitali gioie erotiche e le sue oscure tragedie. Qualcuno lo troverà certamente scandaloso ma, per quanto riguarda la grande arte – citando Pier Paolo Pasolini – scandalizzare è un diritto, scandalizzarsi è un piacere.

Armando Talas

Bacanal: the scandalous spectacular of the Circo de los Horrores

Madrid, on a saturday night at dusk, lights up like many little flames. From the entrance of the chapiteau of the Circo de los Horrores a slight reddish luminiscence slips through, as if the world on the other side had a different colour, a creepy and bright tinge.

Inside, a pianist in an elegant purple attire plays with his deft hands, accompanying the flittering shapes bathed in the soft red lights, who appear on the scene and among the crowd, like ghostly apparitions.

A sensual courtesan accosts me, her horns twisted, her demeanor coquettish, she’s attractive and scary at the same time; not far away, another buxom young lady suddenly lowers the top of her guepiere, showing her three breasts in satisfied glee; on the stage, within the ghastly gates and rattling chains, muscular men tread with their black wings, provocative women in various stages of undress lounge on ottomans, a dwarf is flailing and laughing, while Nebula, Lucifer’s daughter, is leading a half naked slave on chain leash.

But it’s Lucifer who’s the master of this game, the audience hanging from his gravelly, outrageous voice: he provokes, commands, interrogates, plays with the crowd like a cat with the mouse, until he elicits unstoppable laughter, authoritarian and severe like an ancient white clown.

When the laughs wane, the icarian number can begin, because Bacanal is true circus, and it offers technically ardous, highly spectacular feats, adrenalinic exhibitions that mesh well with the dark and erotic atmosphere.

There are obscene coreographies, where elegant and serpentine movements are paired with goliardic, humourous songs, like “Sitophilia”, a hymn to the joys of pairing food and sex. There’s a technically perfect chinese pole number, though a profane may mistake the gorgeous, amazonian performer for an erotic pole dancer. There’s a sensational single-trapeze duo, with writhing dancers simulating intercourse on the giant bed below them, not to mention the sides of the stage, where BDSM play is taking place. It’s quite impossible not to be pleasantly distracted.

By the time El Jefe, Lucifer, calls for the intermission, I know the show is well worth the price of admission.

The second act begins in a darker, creepier tone: a coven of witches is celebrating a sabbath and conjuring a horned figure, reminiscent of Baphomet, the ancient god often assimilated to Satan. Underneath the dark cape, a young man is ready to present an impressive aerial number, flying above the crowd while the witches dance in ecstasy, naked but for the lightest of veils, the frame of their bodies soft as if slightly out of focus, like a delirious vision.

A funereal contorsionist follows, brought to the stage by a handful of frightening plague doctors. A contorsionist’s uncanny movements can prove appalling when framed with the right scene and music: in the most extreme moments, I could hear screams from the crowd, as if they were witnessing bones being broken, joints irrecuperably dislocated.

When Lucifer comes back on stage, he’s ready to celebrate the “wedding of the dark side”: what follows is a desecrating, crass and funny farce where “el Jefe” forces two unwitting members of the audience to confess, in jest, their sexual history, habits and preferences, relationships and love, affinities and differences, in a series of absurd and humourous questions and trials, while the crowd positively howls with laughter. It’s quite difficult to make people laugh while revealing some of the most intimate, private aspects of their life in front of hundreds of complete strangers. When you succeed, the laughs that erupt are light, liberating in the defeat of oppressive modesty and ancestral sin.

The final part of the show does not relent in its rhythm, and offers first an exhibition of funambolism on a slack rope, where the performer astonishes by balancing, feet in the air, on a ladder.

Finally, the show closes with a mano-a-mano number where one of the two performers is disabled, and takes the stage on a wheelchair, in an extraordinary feat of strenght, willpower and resilience that wows and moves the audience.

It is the right occasion, for Lucifer, to give a few wise parting words: that you can change your fate, and overcome hardships; that you must enjoy your present, and not worry too much about the future, and that Bacanal’s true nature is that of a joyous celebration of life in all of its aspects, with its dark tragedies, and its sensous pleasures.

Some may find it scandalous but, like the italian poet Pier Paolo Pasolini once said, to scandalise is a right, to be scandalised is a pleasure.

Article by Armando Talas

Translate by Lara Mancini